As temperature rises and sunny days become more frequent, many people take advantage of the longer daylight hours to spend more time outdoors. Whether it’s a walk in the park, a weekend at the beach, or simply running errands in the sun, it’s important to recognise that certain medications can significantly increase the skin’s sensitivity to ultraviolet (UV) radiation. This often-overlooked side effect, known as drug-induced photosensitivity (DIP), can make even brief periods of sun exposure result in unexpected skin reactions, such as redness, blistering sunburns, itchy rashes, or, in some cases, delayed allergic responses.

While we recently explored the importance of vitamin D supplementation and safe sun exposure in our article, “What’s the Deal with Vitamin D?” it is equally important to be aware of the potential risks associated with drug-induced photosensitivity – particularly during the sunnier months. Striking the right balance between gaining the benefits of sunlight and preventing adverse skin reactions is especially important for individuals taking medications that may alter the skin’s response to UV radiation.

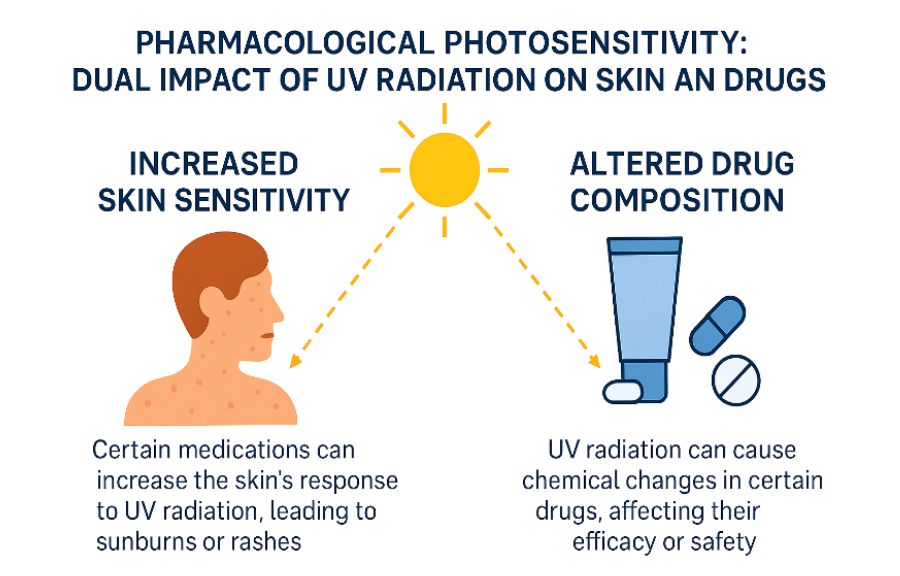

Photosensitivity can occur with a wide range of medications, including many common over-the-counter (OTC) drugs, such as pain relievers, antihistamines, and herbal supplements. Unfortunately, many individuals are unaware that the medication they’re taking – even one as familiar as ibuprofen – could make their skin more vulnerable to sunlight. As a result, mild symptoms may be dismissed as a “regular sunburn,” while more serious reactions can lead to discomfort, delayed diagnosis, or unnecessary concern. Moreover, in certain cases, UV radiation can directly affect the medication itself, especially topically applied products. Sunlight may alter some drugs’ chemical structure, pharmacological activity, or safety profile, leading to reduced therapeutic effect or the formation of irritant or allergenic byproducts. Therefore, understanding both how medications can alter the skin’s response to sunlight and how sunlight can alter medications is essential for safe and effective use.

In this article, we will examine the mechanisms by which UV radiation interacts with certain pharmacological agents, identify commonly used medications associated with photosensitivity, and explore how UV radiation can directly affect certain medications by altering their chemical structure, therapeutic efficacy, or safety profile. We will also present evidence-based strategies to mitigate these risks. Whether you are spending time at the beach, engaging in outdoor activities such as gardening, or simply being exposed to sunlight during daily routines, these recommendations aim to support safe sun practices and minimise the potential for adverse cutaneous reactions linked to medication use.

Drug-Induced Photosensitivity – A Closer Look at Sun-Reactive Skin Reactions

DIP refers to an adverse cutaneous reaction triggered by the interaction between UV radiation – most commonly UVA (320–400 nm) and, to a lesser extent, UVB (280–320 nm) – and certain medications or their metabolites. These substances absorb UV energy and initiate a cascade of skin damage or immune-mediated responses (Di Bartolomeo 2022).

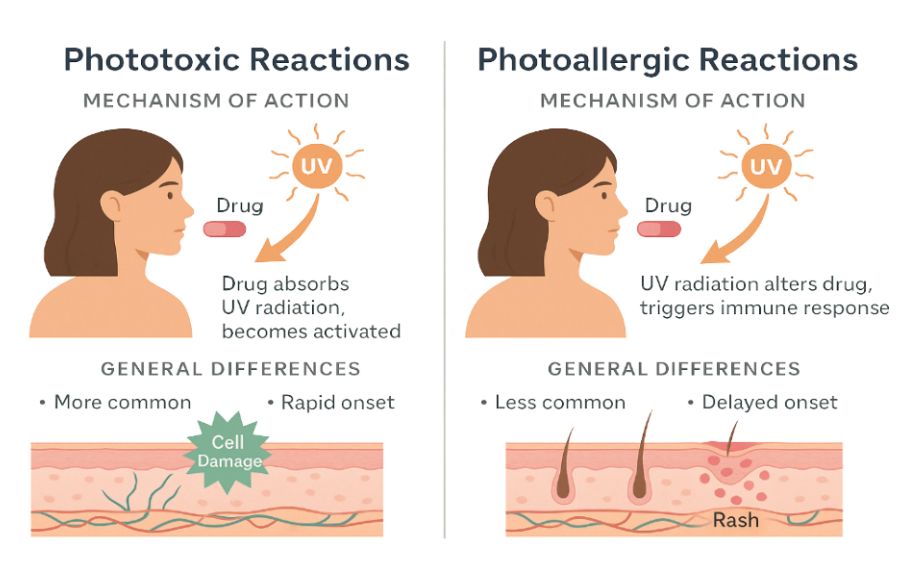

DIP encompasses two primary types of skin reactions:

- Phototoxic reactions are the more common form of DIP and occur when a drug—or its metabolite—absorbs UV light and becomes chemically reactive. This process leads to the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which can damage DNA, lipids, and proteins within the skin, resulting in cellular injury and inflammation (Di Bartolomeo 2022, Mehrholz 2020).

Phototoxic reactions are characterised by a rapid onset, typically developing within minutes to a few hours following sun exposure. Clinically, the reaction resembles a severe sunburn, presenting with erythema, swelling, burning sensations, and, in some cases, blister formation. The reaction is usually confined to sun-exposed areas of the body, such as the face, neck, arms, and hands, where UV radiation directly activates the photosensitising agent. Phototoxicity is generally dose-dependent and may occur upon first exposure to the medication without the need for prior sensitisation (Mehrholz 2020).

- Photoallergic reactions – are less common than phototoxic responses and involve a cell-mediated immune mechanism. These reactions occur when UV radiation alters the structure of a drug or its metabolite, causing it to behave like an antigen. This modified compound then triggers a type IV delayed hypersensitivity reaction, resulting in an immune-mediated inflammatory response in the skin (Mehrholz 2020).

Overview of Common Photosensitising Medications

Both phototoxic and photoallergic reactions have different underlying causes and may appear in various ways on the skin. Photosensitivity reactions can manifest as a range of cutaneous symptoms, from mild erythema and sunburn-like irritation to more severe conditions such as rashes, blistering, peeling, or eczema-like lesions. In some cases, these reactions may lead to hyperpigmentation, scarring, or prolonged inflammation – especially if sun exposure is repeated or the reaction is not recognised and managed early. These reactions can significantly affect a person’s comfort, self-confidence, and even their willingness to continue using the medication (Di Bartolomeo 2022).

Importantly, DIP is not limited to prescription drugs. Many common OTC medications and herbal supplements can also increase the skin’s sensitivity to sunlight. The risk becomes particularly relevant during the summer months or when spending extended periods outdoors (Montgomery and Worswick 2021).

Knowing which medications carry this risk – and taking simple precautions – can make a big difference.

Below are some common categories of photosensitising drugs, along with examples:

| Drug Class | Example of an active substance | Type of Photosensitivity | Clinical Features |

| NSAIDs | Ibuprofen ⚠ (OTC) Ketoprofen ⚠ (OTC) Naproxen ⚠ (OTC) | Phototoxic | Redness, swelling, and sunburn-like symptoms on sun-exposed areas |

| Antibiotics | Doxycycline Ciprofloxacin Sulfamethoxazole | Phototoxic | Intense sunburns, erythema, and blistering—especially on the face and arms |

| Antidepressants | Amitriptyline Imipramine Sertraline | Phototoxic / Photoallergic | Photosensitive dermatitis, rash, and occasionally delayed eczematous lesions |

| Diuretics | Hydrochlorothiazide | Photoallergic | Eczema-like eruptions, itching, redness; hyperpigmentation in chronic cases |

| Antihistamines | Diphenhydramine ⚠ (OTC) | Phototoxic | Sunburn-like reactions, pruritus, and erythematous rashes |

| Antifungals | Voriconazole | Phototoxic | Severe sunburn and potential long-term skin damage |

| Herbal Supplements | St. John’s Wort ⚠ (OTC) | Phototoxic | Burning, redness, and blistering after minimal UV exposure |

These examples underscore just how important it is to raise awareness about DIP – not just among healthcare professionals but also among patients and everyday users of common medications. Many people don’t realise that the medication they take for pain, allergies, infections, or even anxiety might make their skin more vulnerable to sunlight.

Photolabile drugs and UV-induced reactions: a clinical insight into topical therapy risks

UV radiation can also directly affect the medication itself, particularly topically applied products. When exposed to sunlight, some medications undergo photochemical transformations that can alter their chemical structure, reduce their pharmacological efficacy, or generate reactive byproducts that are irritating or immunogenic. These changes may lead to unexpected skin reactions, loss of therapeutic benefit, or increased risk of sensitisation, making sun protection a crucial consideration during treatment (Ahmed 2016).

One of the most well-documented examples is ketoprofen gel, a topical NSAID commonly prescribed for localised musculoskeletal pain (Lodén 2004). While effective in alleviating inflammation and discomfort, ketoprofen is also recognised as one of the most photoallergenic NSAIDs. Upon exposure to UVA radiation, ketoprofen undergoes photochemical degradation, resulting in the formation of benzophenone-like photoactive compounds. These reactive derivatives can bind to skin proteins, forming haptens that elicit delayed-type hypersensitivity (type IV) reactions. Clinically, this presents as severe photoallergic dermatitis, characterised by eczema-like eruptions, erythema, pruritus, and, in some cases, vesicles or bullae, which may extend beyond the application site. The inflammatory reaction can persist for several weeks and often recurs upon re-exposure, even after discontinuation of the drug, due to long-lasting cutaneous sensitisation.

Another notable example is tretinoin (all-trans-retinoic acid), a vitamin A derivative used topically for treating acne, photoaging, and hyperpigmentation disorders (Motamedi 2021). Tretinoin is highly photolabile—its molecular structure is unstable under UV radiation, particularly UVB. Upon exposure to sunlight, tretinoin rapidly degrades into less active or inactive metabolites, thereby reducing its therapeutic efficacy. In addition, tretinoin promotes epidermal turnover and thins the stratum corneum, increasing the skin’s susceptibility to sunburn and irritation. Due to these properties, tretinoin is typically recommended for evening application, with strict avoidance of sun exposure and consistent use of broad-spectrum sunscreen during the day to minimise the risk of phototoxic reactions and maintain treatment effectiveness.

Even compounds formulated to protect the skin from sunlight, such as chemical UV filters, can paradoxically contribute to photosensitivity in susceptible individuals (Ahmed 2016). A notable example is oxybenzone, a widely used broad-spectrum sunscreen agent found in many over-the-counter sun care products. While effective at absorbing both UVA and UVB radiation, oxybenzone has the ability to penetrate the skin barrier and, upon UV exposure, generate ROS and photoproducts capable of inducing photoallergic dermatitis. Clinically, such reactions may present as erythema, pruritus, and eczematous eruptions localised to the areas where the sunscreen was applied. These responses are typically immune-mediated, resembling allergic contact dermatitis, with a delayed onset ranging from hours to days post-exposure. In addition to its photoallergic potential, oxybenzone has been subject to scrutiny for its systemic absorption and endocrine-disrupting effects, prompting regulatory reviews and leading some countries and manufacturers to seek safer alternatives in modern photoprotection formulations. We discussed the role, safety, and controversies surrounding UV filters in more detail in our article “Unmasking UV Filters: What’s Really in Your SPF?”.

These examples underscore the importance of photostability in dermatologic formulations and highlight the dual risk associated with certain topical therapies: not only can they sensitise the skin to UV radiation, but their own chemical stability and safety profile may be compromised by sun exposure.

Drug + Sunlight = Skin Trouble: Here’s Why You Should Report It

DIP is a clinically relevant yet frequently under-recognized type of adverse drug reaction (ADR). Despite being preventable in many cases, DIP continues to be underreported, partly due to its variable clinical presentation and delayed onset. Symptoms may mimic ordinary sunburn, allergic dermatitis, or chronic eczema and often appear with a delay after sun exposure. This can result in DIP being misdiagnosed or entirely overlooked – by both patients and healthcare professionals. Moreover, DIP is sometimes mistakenly attributed to other environmental factors or skin conditions, further obscuring its true incidence (Ge 2025).

Why reporting DIP matters ?

Prompt and accurate reporting of DIP is essential to:

- Enhancing pharmacovigilance systems – DIP reports contribute to national and European safety databases such as EudraVigilance, helping build a more complete picture of adverse drug effects. These real-world data are vital for identifying new safety signals and confirming known risks across diverse populations.

- Calling for regulatory action – Spontaneous reports of DIP can prompt regulatory authorities such as the European Medicines Agency (EMA) or national competent authorities to evaluate the need for label updates, including additions to the Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC) or Package Leaflets (PLs). In some cases, reports may lead to the implementation of risk minimisation measures such as warnings, contraindications, or changes in dosing recommendations.

Examples of how photosensitivity risks are communicated in the PL (in line with EMA Working Group on Quality Review of Documents (QRD)):

Section 2 of PL – What you need to know before taking [product name]:

“Avoid sunbathing or using tanning beds while using this medicine.”

Section 4 of PL – Possible side effects:

It should describe the nature of the photosensitivity reactions and instructions on what to do if they occur.

Section 5 of PL – How to store

Photolabile medicines may require clear instructions e.g.: “Keep this medicine in its original packaging to protect it from light.”

Protecting patient safety

When photosensitivity risks are clearly identified and communicated, healthcare professionals can better counsel patients on preventive strategies – such as applying broad-spectrum sunscreens, avoiding sun exposure during peak hours, and using protective clothing. This allows patients to continue necessary therapies while minimising dermatological risks.

Identifying emerging trends

Reporting helps flag previously unrecognised photosensitising properties in newly authorised drugs or formulations, especially those used chronically or in combination with other sensitising agents. It also sheds light on the cumulative impact of long-term exposure, which may only become evident after extended use in a real-world setting.

Effective communication of photosensitivity risks is not only a regulatory obligation – it is a cornerstone of safe and informed medicine use. One of the key tools enabling this communication is properly prepared Product Information, developed during the pre-authorisation stage of a medicinal product. By adhering to EU guidelines and incorporating QRD-compliant phrasing into documents such as the Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC) and the Package Leaflet (PL), Marketing Authorisation Holders can ensure that patients and healthcare professionals are adequately informed and better protected against preventable photoreactions.

How can you protect yourself while taking photosensitising or photolabile medications?

If you’re using one of the medications listed in this article or planning to start – there’s no need to avoid the outdoors entirely. However, it is essential to take proactive steps to minimise the risk of phototoxic or photoallergic skin reactions. These precautions not only help prevent skin discomfort but also support the effectiveness and safety of your treatment.

Here’s how you can enjoy the sun safely while taking photosensitising medications:

Read the leaflet or ask a pharmacist.

Always read the PL that comes with your medication. Look for warnings such as “may cause photosensitivity” or “avoid prolonged sun exposure.” If you’re unsure about the risks, don’t hesitate to consult your pharmacist or doctor, especially when starting a new medication or using topical formulations like gels, creams, or ointments.

Use a broad-spectrum sunscreen daily.

Apply a broad-spectrum sunscreen with SPF 30 or higher that offers protection against both UVA and UVB rays. Reapply every 2 hours and immediately after swimming, sweating, or towel drying.

Limit sun exposure during peak hours.

Avoid being outdoors during the peak UV radiation hours (10 a.m. to 4 p.m.). If outdoor activity is necessary, seek shade whenever possible and try to schedule errands or exercise for early morning or late afternoon.

Be cautious with topical products. Topical medications such as ketoprofen gel, tretinoin, and certain acne treatments are particularly susceptible to UV-induced chemical changes. Avoid applying these products immediately before sun exposure, and use them in the evening when appropriate. Always wash your hands thoroughly after application.

Wear protective clothing.

Wear lightweight, long-sleeved clothing, wide-brimmed hats, and UV-blocking sunglasses. Consider garments labelled with a UV protection factor (UPF) rating for added reassurance.

Stay hydrated and monitor your skin.

Photosensitising drugs can exacerbate dryness, redness, or skin peeling. Be sure to drink plenty of water and moisturise regularly to help maintain your skin’s natural barrier. If you notice new rashes, blisters, or severe redness, stop sun exposure immediately and consult a pharmacist or doctor.

Photosensitivity may seem like a minor issue – an occasional rash or a bit of redness but in reality, it can significantly affect your skin health, daily comfort, and even your willingness to continue with prescribed treatments. In some cases, it can lead to severe sunburn-like reactions, persistent pigmentation changes, or eczema-like eruptions that are painful, unsightly, and distressing.

The good news is that many of these reactions are preventable with the proper knowledge and a few simple precautions. Whether taking a common OTC painkiller, applying a topical acne treatment, or starting a new prescription drug, understanding how your medications might interact with UV radiation is the first step toward staying safe.

Being informed about DIP empowers you to make smarter choices, such as applying medications in the evening, using a broad-spectrum sunscreen, wearing protective clothing, and always checking the PL for sun-exposure warnings. These small but important steps can make a big difference in protecting your skin and maintaining the safety and effectiveness of your treatment.

So, as you enjoy the brighter, warmer months ahead, let the sunshine in but do so wisely. With a bit of foresight and care, you can safely protect your skin, avoid unnecessary discomfort, and make the most of your summer.